Understanding HIV: Early Indicators and Key Factors in Its Progression

Many people associate HIV with severe illness, yet in its earliest stages the virus often causes only subtle or easily overlooked changes in the body. Recognizing early indicators, understanding why symptoms may go unnoticed, and knowing how overall health and lifestyle influence immune function can help people have more informed conversations with healthcare professionals and make timely decisions about testing and care.

Human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, affects the immune system in ways that can be gradual, complex, and different from one person to another. Early changes may be mild, and the long course of infection can make it hard to see how the virus progresses over time. By looking closely at early indicators, why symptoms can be missed, and how the body responds to viral stress, it becomes easier to understand what is happening inside the immune system.

This article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Please consult a qualified healthcare professional for personalized guidance and treatment.

What are the early indicators of HIV

In the first few weeks after infection, some people experience a group of symptoms often described as acute HIV infection or early HIV illness. These symptoms can resemble a seasonal viral infection. They may include fever, fatigue, sore throat, swollen lymph nodes, skin rash, muscle aches, headaches, and sometimes mouth ulcers. Not everyone has all of these symptoms, and some people have none at all.

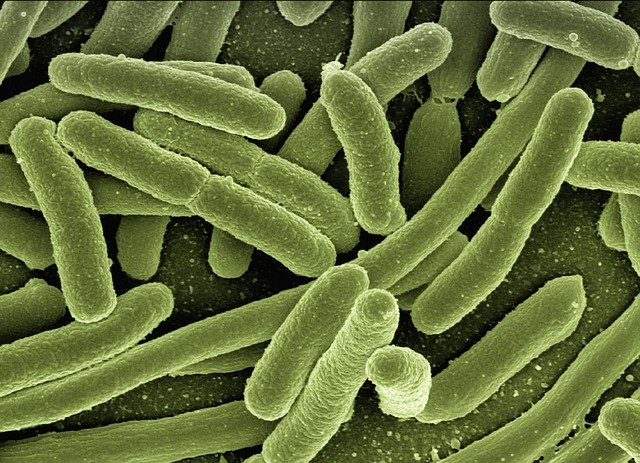

These early signs appear as the virus spreads rapidly in the body and the immune system mounts its first strong response. During this stage, the amount of virus in the blood can be very high, which also means a higher chance of passing the virus to others. Because the symptoms are not unique to HIV, testing is the only way to know whether HIV infection is present.

Why HIV symptoms often go unnoticed

HIV symptoms often go unnoticed for several reasons. First, early symptoms look similar to many common infections that resolve on their own, such as influenza or other respiratory viruses. People may treat the illness at home with rest and fluids, never suspecting HIV as a possible cause.

Second, after the early phase, symptoms may lessen or disappear for a long period. This stage is sometimes called chronic HIV infection. The virus is still active but replicates at lower levels. Many people feel generally well and may not connect occasional fatigue or mild symptoms with a serious underlying infection. Because there is no single classic symptom pattern, especially in the early years, people often assume they are healthy unless they are tested.

How lifestyle and health factors affect immune function

The progression of HIV is closely linked to the health of the immune system, and many lifestyle and health factors can influence immune function. Nutrition, sleep quality, physical activity, mental health, and the presence of other infections all play a role in how well the body responds to HIV.

A balanced diet and adequate protein can support the production and repair of immune cells. Regular, moderate physical activity is associated with better cardiovascular and immune health. On the other hand, chronic stress, untreated depression or anxiety, smoking, heavy alcohol use, and certain drugs can place additional strain on the immune system. Other infections, such as sexually transmitted infections or hepatitis, may further challenge immune defenses and can complicate the clinical picture.

While healthy habits cannot eliminate HIV, they can support overall immune health and complement medical care. People living with HIV who maintain consistent medical follow up and adopt supportive lifestyle habits may help their bodies cope better with ongoing immune stress.

Understanding how the body responds to viral stress

HIV targets specific immune cells that coordinate the body response to infections. Over time, as the virus continues to replicate, the number and function of these cells can decline. The immune system may still manage many daily challenges, but its capacity becomes gradually reduced. This process is often monitored with blood tests that assess key immune cell levels and the amount of virus present.

Viral stress does not act alone. The body response also includes inflammation, which is part of the normal defense system. When inflammation becomes long lasting, it can contribute to fatigue, weight changes, and increased risk of other health conditions. In the setting of HIV, long term viral stress and inflammation can influence how quickly symptoms appear and how severe they become.

Understanding this balance between virus, immune cells, and inflammation helps explain why progression varies from person to person. Some individuals may experience slower changes, while others may see a faster decline in immune function if the virus is not controlled.

Progression, monitoring, and the importance of early awareness

As HIV progresses without treatment, the immune system becomes less able to fight infections and certain cancers. People may develop more frequent or severe infections, unexplained weight loss, persistent fevers or night sweats, chronic diarrhea, or long lasting swollen lymph nodes. These later signs reflect more advanced immune damage.

Regular medical monitoring allows healthcare professionals to track changes in immune function and viral levels over time. Early awareness of potential exposure, recognition of early indicators, and timely testing can help identify HIV before significant immune damage takes place. Once HIV is identified, ongoing collaboration with a healthcare team and attention to overall health can support the immune system and help manage the long term effects of viral stress.

By understanding how early symptoms may look, why they are often overlooked, and how lifestyle and immune function interact, people can approach HIV with more clarity. This knowledge can support more informed discussions with healthcare professionals and a better grasp of how the body responds over time to a chronic viral infection.